Japan is a land where tradition and modernity often blend seamlessly, creating spaces that evoke deep contemplation and awe. This balance is nowhere more apparent than in the incredible work of Tadao Ando, an architect whose minimalist, concrete structures have become iconic in the world of modern architecture.

Recently, I embarked on a journey to two islands in Japan – Awaji Island and Naoshima – each home to some of Ando’s most celebrated works. This trip was not just about visiting buildings; it was about experiencing spaces that challenge, soothe, and inspire the soul.

Table of Contents

Awaji Island

My journey began on Awaji Island, a lush island known for its natural beauty and tranquil atmosphere. Here, Ando’s work is a dialogue with the surrounding landscape, each structure a testament to his belief that architecture should coexist harmoniously with nature.

The Water Temple (Honpukuji)

My first stop was the Water Temple (Honpukuji), a place where the sacred and the serene meet. As I approached the temple, I was greeted not by towering walls or ornate gates but by a serene lotus pond. The entrance to the temple is hidden beneath this water feature, requiring visitors to descend into the earth – a symbolic journey inward.

The temple itself is a simple, circular concrete structure, its austerity softened by the light filtering through the skylight above. Sitting inside, I felt a deep sense of calmness, as if the world outside had melted away, leaving only the quiet hum of my own thoughts. This moment of self-reflection and inner peace was so great that I felt a kind of awakening that lingered and pervaded my whole trip.

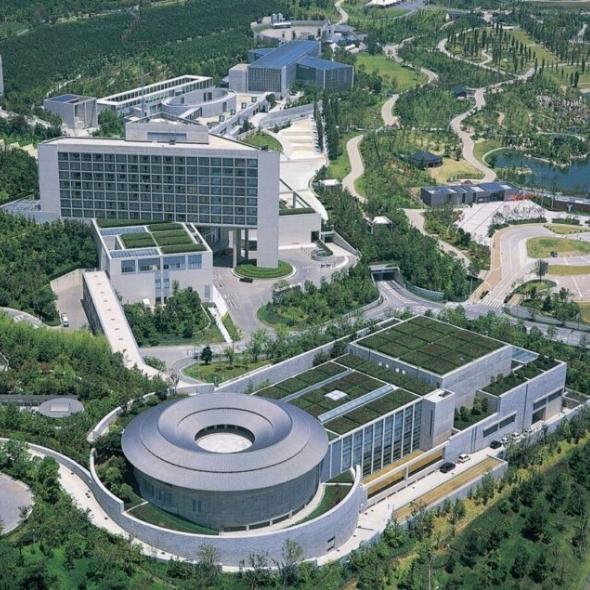

Awaji Yumebutai

Next on my itinerary was Yumebutai, a sprawling complex that includes a conference centre, office space, hotel, indoor and outdoor gardens, amphitheatre, and parkland. The location for this build was of great interest to me. The land had been cleared following a devastating earthquake in the area. The debris was used to create the artificial island that became Kansai International Airport, leaving a huge wound in the hillside.

Ando didn’t hesitate in choosing the site for his masterpiece, and Yumebutai is his tribute to the resilience of the human spirit and the healing power of nature. There can be no doubt too, that this amazing build ‘healed’ the wounded hillside

The complex is a labyrinth of terraces, reflecting pools, and gardens, all arranged in a way that invites exploration. As I wandered through the vast complex, I marvelled at how Ando has used concrete—often perceived as cold and unforgiving—to create a space that felt alive, warm, and connected to the earth. The use of water, plants, and natural light throughout the complex is masterful, turning what could have been a sombre monument into a vibrant celebration of life. An absolute must-visit.

The Seawind Hotel

My third Awaji stop is often overlooked, even by Ando aficionados. I overnighted at the Seawind hotel, a fascinating Ando design perched high on a cliff overlooking the eastern coast. The hotel was built with an awareness of the harmony between people and nature, and in this beautiful location, visitors can grasp at this connection as they admire the sea, greenery, and the architectural beauty all around.

The lobby in particular is a must-see. It’s located at the end of a grand staircase, where the view of the beautiful Osaka Bay is framed perfectly by the huge windows there. It is truly a stunning sight.

Naoshima

From Awaji Island, I traveled to Naoshima (via Takamatsu in Kagawa), an island that, over the past 20 years or so, has transformed into a hub for contemporary art. Here, Ando’s architecture takes on a different role—one of framing and enhancing the experience of art.

The Benesse House

The centerpiece of Ando’s work on Naoshima is the Benesse House, a combination of museum, hotel, and art gallery. Unlike the buildings on Awaji Island, which are deeply embedded in the landscape, Benesse House stands apart, a stark concrete structure perched on the edge of the sea. The building’s design is simple and geometric, yet its impact is profound.

Walking through the museum, I was struck by how Ando has used the play of light and shadow to guide our attention, not just to the artworks on display, but to the spaces between them. The architecture here doesn’t compete with the art; instead, it creates a meditative environment where each piece can be fully appreciated.

The Chichu Art Museum

A short distance from Benesse House is the Chichu Art Museum, perhaps Ando’s most ambitious project on the island. Built almost entirely underground, the museum challenges conventional ideas of what a gallery should be. The entrance is an unassuming staircase leading down into the earth, a journey that felt like descending into another world. Inside, the museum is a series of stark, concrete rooms, each designed to house a specific work of art.

The most stunning of these is the room dedicated to Claude Monet’s Water Lilies, where natural light from above creates an ever-changing environment that shifts with the time of day and the seasons. Ando’s use of light here is nothing short of genius, turning the room itself into a living, breathing artwork.

Comparison of Architecture between Awaji Island and Naoshima

While experiencing Ando’s work on these two islands, I was struck by how different – and yet how similar – his approach is in each location. On Awaji Island, his buildings are rooted in the landscape, using natural elements like water and greenery to create spaces that feel organic and alive. The architecture here is about healing and contemplation, offering visitors a chance to reconnect with nature and themselves.

In contrast, Ando’s work on Naoshima is more about isolation and introspection. The stark, geometric forms of the buildings create a sense of distance from the natural world, focusing attention inward, on the art and the self. Yet, even here, Ando’s use of natural light and carefully framed views of the sea remind us of our connection to the world outside.

The impact of Ando’s architecture in both places is profound, but it manifests in different ways. On Awaji Island, his buildings invite us to lose ourselves in nature, to find peace in the harmony between the built and the natural. On Naoshima, his work challenges us to confront the solitude of the human experience, to find meaning in the spaces between art and life.

Conclusion: A Journey of Discovery

My journey to Awaji Island and Naoshima was more than just an architectural tour; it was a voyage of self-discovery. Through Ando’s buildings, I explored not just the physical spaces of Japan’s islands, but also the inner landscapes of thought and emotion. His work, at once austere and inviting, serves as a reminder that architecture is not just about creating spaces—it’s about shaping experiences, provoking reflection, and, ultimately, touching the soul.

It was just a 2-day trip for me this time, but there are several other amazing spots in the area that could added to make a more comprehensive journey into the architecture of the region. Here are my tips:

Naoshima

1. Lee Ufan Museum

– Architect: Tadao Ando (collaboration with artist Lee Ufan)

2. Minamidera

– Architect: Tadao Ando (with artist James Turrell)

3. Naoshima Bath “I ♥︎ Yu”

– Architect: Shinro Ohtake

Teshima

4. Teshima Art Museum (Teshima Island)

– Architect: Ryue Nishizawa

5. Les Archives du Cœur (Teshima Island)

– Architect: Tadao Ando

Awaji Island

6. Zenbo Seinei

– Location: Awajishima, Japan

– Architect: Shigeru Ban

7. Haru San San

– Location: Awajishima, Japan

– Architect: Shigeru Ban

8. Awaji Student War Memorial

– Location: Awajishima, Japan

– Architect: Kenzo Tange